Interesting tidbits about the Hampton Chapter, our Patriots and our Daughters.

PATRIOT MINUTES FROM HAMPTON DAUGHTERS

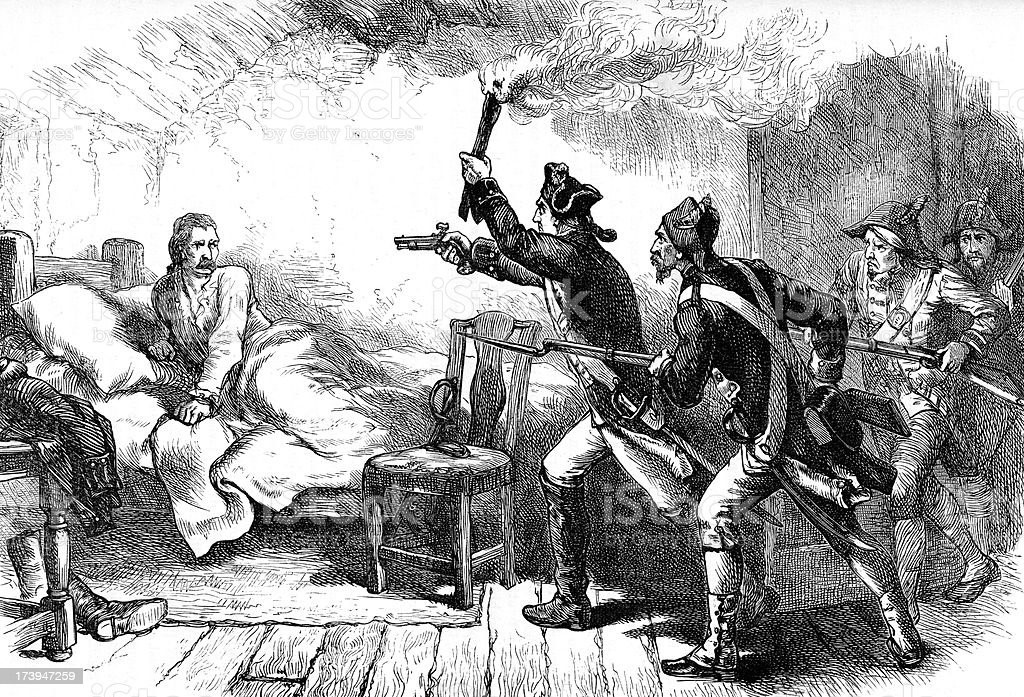

Caption – British Brig. Gen. Richard Prescott shown captured unceremoniously by Patriot Rhode Island forces in a vintage print.

When Virginia’s Hampton Chapter invited members to share a “Monthly Patriot Minute,” they were assured it could be a short summary of a Patriot, or something related to the Patriot’s service. And it very quickly became apparent that those from whom we descended found themselves doing ordinary things in some very extraordinary circumstances, surrounded by the people and events that make it into history books, even if they did not, providing rare insights into the larger issues and bigger personalities of the Revolutionary War.

Chaplain Dianne Pons got the ball rolling with Pvt. James Weaver, a member of the Rhode Island Brigade, who participated in one of the outstanding special operations of the war when a group of volunteers joined Lieutenant Colonel William Barton to capture of Brigadier General Richard Prescott, commander of the British forces, near Newport in 1777. Using whaleboats and the dark of night, Gen. Prescott was kidnapped from his bed and taken away in nightshirt and slippers before anyone attempted to rescue him. He was later used in a prisoner exchange of the previously captured Patriot General Charles Lee.

Treasurer Jenny Weibke followed the next month with a young farmer, Pvt. Notley Tippett, who served nine months with the St. Mary’s County (MD) Militia and was recruited to join the colorful Count Casimir Pulaski’s legion. Pulaski, a Polish nobleman known as one of the founders of the American Cavalry, was in exile in France when Benjamin Franklin recruited him to join the American Cause. He served with General Washington, formed the Continental Army cavalry of just a few hundred men comprised of Americans like Tippett, French, Poles and deserting Hessian mercenaries. Tippett was honorably discharged from the First Maryland Line, and reenlisted to continue serving until 1783.

Historian Donna Farrell went westward, where Pvt. John Kersey participated in the War as a 16-year-old frontiersman in the Virginia Militia as part of Col. Daniel Boone’s Regiment, in Kentucky County. Kersey joined the militia as a soldier and Indian scout, where Patriotic fervor against the British was often subordinate to the complicated issues and tensions between incoming pioneers and the indigenous people already living there, especially the splintered Shawnee, and the pressures that colonial incursion put upon threatened lands and cultures.

Another layer of history was added by Regent Sherrie Hurst, who is currently researching Sam Illingworth, a contemporary of her Connecticut Patriot Pvt. George Batterson. The challenge with Illingworth is that he arrived in America as a member of a British Unit assigned to Upstate New York. Separated from his unit, he became lost in a swamp and was found badly in need of food and water by Americans who helped him recover, by which time the British Army had left the area and Sam decided to stay in New York. He eventually farmed in a remote area of Lewis County, operated a ferry across the river, and became an American citizen in 1812, at which time he swore allegiance to the United States and to the state of New York. If a “last act” can be found for Sam Illingworth during the Revolutionary War time period showing service to the Cause, he may one day join the ranks of DAR Verified Patriots, despite his dubious beginning.

THE STORIES WE HAVE LOST

The search began simply enough. The Regents of the Hampton (Virginia) Chapter, established in 1900, nine years after the founding of the National Society, was a list of ladies without first names, but designated as the Mrs. of their husbands. But the second Regent, from 1902-03, claimed both her name and her title, Dr. Frances Weidner, and the chapter wanted to know more about her. The search has been both inspiring and frustrating.

Dr. Weidner was a medical doctor, a graduate of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, Class of 1888. City directories indicate she lived in Tidewater Virginia through most of the first decade of the 20th century, where she served as what was variously described as Director, Superintendent and/or Physician in Charge of the Dixie Hospital and Training School for Colored Nurses. The school had been created on the campus of Hampton Institute in 1892 as a combination nursing school for black women and a two-room clinic for the families living near the Institute, many of which were descendants of enslaved families, extremely poor, with high rates of chronic illness.

But what else do we know about Dr. Weidner? Very little, unfortunately, despite her being a professional woman of accomplishment. Born in 1867, she was fifth of sixth children, and youngest of the three daughters, of Charles Augustus and Helen Eliza Safford Weidner, in Chester, Delaware County, Pennsylvania. There was obvious pride in the Revolutionary War ancestry of her mother, and all three sisters became early Daughters of the American Revolution based on the service of Patriots John Norton, Silas Safford and William Cabell. “Fannie’s” full name, in fact, was Frances Norton Weidner after the Vermont Patriot. Her education and accomplishments in the late 19th and early 20th centuries are impressive, and her father’s will, which leaves his “paintings and engravings” to her, as opposed to the cash left to other siblings, perhaps reflects her aesthetic and artistic interests as well.

By 1913 she had returned to Pennsylvania, and was a member of the Delaware County Medical Society, an officer of that Society. She went to New York City for a time, returning to Pennsylvania in 1917, then back to Manhattan where she married Francisco Diez on February 1, 1919. Mr. Diez was a native of Madrid, Spain, who had come to the United States in 1913. In the 1920 Census, they are recorded as renting in Manhattan, where his occupation is a translator, and hers a physician. In the 1921 American Medical Directory, Dr. Frances Weidner Diez is still a member of the Medical Society of the State of Pennsylvania, “not in practice,” and living in Manhattan.

And then . . . nothing. No children, no divorces, no deaths or burial records. A 1970 compilation of alumnae of the medical school includes her among the deceased with the surname of Diez-Weidner. Perhaps she and her husband returned to Europe, where his homeland of Spain had remained neutral during World War I and the Spanish Civil War was more than a decade in the future. Or perhaps the stories and records of a woman and her immigrant husband, no matter how significant, have simply been lost to time.

______________________________________________________________

HIDDEN DAUGHTERS

The Hampton Chapter of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) is proud to salute Daughters Nancy Jane Bains and Sue S. Miserentino, two of our own, who served our country as “human computers.”

Women began computing work at the National Advisory Council for Aeronautics (NACA) in 1939. After World War II, the United States’ focus shifted from the war effort to the goal of supersonic flight. In 1958, NACA became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). At that time, NASA officially ended racial segregation of employees within the organization.

Answering the call of recruiters, or responding to newspapers that were advertising jobs with “no degree required” – a standard code for work for which women could apply — women had joined NACA. If they did not have a degree, the government sent them to universities to obtain one. These women took pride in work others considered dull, rote, unskilled, tedious, repetitive, and minutely detailed. Their work, considered unsuitable for men, earned half the pay of male colleagues.

Women, segregated by race initially, with dedicated mathematical and scientific minds, computed millions of numbers by hand, supporting the United States space program. They were known as the “computers” and later appreciatively called “human computers,” working diligently with pride in their hearts for their country, the stars as a goal.

Nancy Jane Bains first worked at NACA the summer of 1957 while in college, and began full-time work with the title of Mathematician at NASA in 1958; Sue S. Miserentino (Past Chapter Regent) also joined NACA in 1958, the same year it became NASA. Sue served as Mathematician in the “16 Wind Tunnel” initiative, assisting engineers.

As Nancy explained, women were originally assigned to “computing sections” within work division. “We were humans doing computing work, so that is where the name human computers came from. Shortly, mathematicians were moved into branches with engineers and other scientists, and there were no more computing sections. With the advent of, first, mainframe computers that took up whole buildings, to desktop computers, and even handheld computers, now mathematicians, engineers and scientists all do NASA’s computing work!”

Sue added that “in our group, the engineers referred to us as ‘the girls’.”

Here in Hampton, Virginia, where America’s space program was launched, we are proud to honor the women whose talents and skills were crucial during those early days in space pioneering. Nancy Jane Bains and Sue S. Miserentino, thank you for your contributions to the nation’s success.

# # # # #